1. Introduction

Examining how both second and foreign language (S/FL) teachers and students negotiate, (re)construct, and resist their social class identities seems to be a slippery topic in S/FL educational and identity research agendas (De Costa & Green-Eneix, 2021; Block, 2012). In a socially stratified world filled with global capitalist and neoliberal ideologies of marketization, commodification, individualist spirit, and economic competitiveness, the place of English as an S/FL teaching and learning tool is at stake. Antecedents such as English as an international language and its global power bring about negative economic, cultural and social implications. These end up affecting the development of the teaching and learning experiences of both students and teachers of ES/FL, as well as the way they discursively self-position and position their fellow stakeholders. The resulting (self) positionings and (self) perceptions, emerging from a dominant foreign language structure mediating pupils’ economic, cultural, and social phenomena related to social class, lead to the reproduction of worldwide class-based inequalities in different types of educational scenarios such as the classroom, the school, and the educational systems. This also leads to differential treatment and unequal language learning opportunities. Likewise, they fiercely impact students and teachers by posing a significant threat to their life trajectories and vital decisions inside and outside school settings (Norton, 2019).

S/FL and identity research have greatly explored the dimensions of gender (Castañeda-Peña, 2021; Knisely & Paiz, 2021), race (Von Esch et al., 2020; Bonilla-Medina et al., 2021), ethnicity (Jiang et al., 2020), and sexuality (Lawrence & Nagashima, 2020; Butler, 2021). Nevertheless, there has been little concern about studies focusing on economic notions and inequalities based on material, social and cultural resources in a society with great socioeconomic stratification and class injustice (Fraser, 2020). Thus, social class identities and discourses have remained underexplored in the field of SLA/L and FL education (Block, 2020; Gao, 2010; Liu & Darvin, 2024), and the lack of attention to this social category is even more noticeable in the FL contexts of Latin America and the Caribbean.

Addressing social class becomes paramount nowadays in a world pervaded by social, historical, political and economic events. An example is the neoliberal ideologies and discourses of marketization, commodification, privatization, individualism, entrepreneurship, consumerism and economic competitiveness that ultimately portray language as a commodity and impinge on English as foreign language learners’ social identities. Another example is globalization, which, on the one hand, has contributed to the global power of English leading to commonly held associations of English with notions of global citizenship.

On the other hand, it has increased the mobility of individuals, capital, goods, and commodities (Kramsch, 2019). This results in diverse FL classrooms occupied by learners with diverse social class backgrounds, students with cosmopolitan and global memberships, and multilingual learners. Such diversity can be a factor that unleashes unequal power relations based on social classes as not all learners in the classroom are multilingual, have a global membership, or share the same socioeconomic conditions.

These phenomena have somehow contributed to widening the gap between the small classes with more capital and the greater classes with less power (Lansley, 2019). Hence, a panorama with more visible social stratification is created wherein class-based inequalities stand out and widen hidden relations of unequal power (Vanke, 2023) and social, cultural, and economic capital not only within the same S/FL classroom but also outside it. The class-based inequalities in a socioeconomically stratified world like the one described are reproduced as a school culture at both institutional and classroom levels. Such social class discourses and identities converging in said educational settings end up affecting the significance of students’ life trajectories, decisions, and opportunities inside and outside the school setting (Hunt & Seiver, 2017).

Although the previous landscape seems to make economic issues more salient, culture and social relations play a vital role as well. The individualist, competitive, entrepreneurial spirit of neoliberal and global capitalist ideologies, heightened by the effect of social networking sites’ materialist and consumerist discourses of influential characters, impinge and conflict with larger society as well as the criteria of communication accession to current novel linguistic pacts of power. These end up affecting unfavorably EFL learners’ attitudes, cultural practices, and lived experiences. Likewise, these cultural practices are shared in relation to others in and outside the classroom. Usually, those others with whom learners share such practices are subjects who share similar social, cultural, and economic practices as well as voluntary affiliations. These groups of subjects form and enact distinctive sociocultural practices encompassing thus a class habitus (Gilleard, 2020).

2. Defining and problematizing Social Class and Social Class Identities

Given the complexity of current society, it is necessary to consider contemporary definitions of social class as different from the pioneer conceptualizations. Marx’s (2020) view of social class as rooted in people’s relationship to and ownership of the modes of material production and Weber’s (2019) notion of shared controls on goods and services consumption, means of production, exchange of assets, and his view on the role of the state in the validation of the education system and policies are quite different from more recent definitions of this social category. Class has been deemed more than an economic and demographic category in the past four decades. This paper shares such conceptualizations which consider the social-culture-economic phenomena and enacted practices of agents (Gilleard, 2020) that ultimately affect education stakeholders besides the long-standing educational system’s role in the decisions on the material, cultural, and symbolic-linguistic assets transformed or reproduced in the teaching-learning process. Social class then entails not only income, occupation, and material possessions but also connections with networks of powerful people that help individuals gain prestige and advantage, educational qualifications, body movements, accent, and consumption and behavior patterns such as engagement in particular pastimes and cultural activities (Bourdieu, 1986; Block, 2012). This study resists regarding social class as a fixed category placed within a social stratifying and demographic structure such as those of working class, middle class and upper class. Instead, it deems it as residing in subjects’ histories, lived experiences, culture, self-identifications, and enacted practices.

Although few studies have undertaken a definition of social class identities due to the lack of attention it has received in the field (Ardoin, 2021; Block, 2020; Hunt & Seiver, 2017; Jones, 2019), some authors deem them as relational, fluid, performed locally, and socially constructed, changing according to time and context and contingent on different factors involving a sense of belongingness and awareness of socioeconomic inequalities and beyond (Pérez & Andrade, 2021; Stubager & Harris, 2022; Thein et al., 2012). Despite these constructions on social class, some studies, as will be seen in the review of scholarly work on this social category, do not conceptualize and address it by examining the dynamics of power relations, class subject positions, negotiation, resistance and construction of class positionings, class-based discursive practices embedded in interaction, class-based lived experiences, and struggles for symbolic capital that emerge in the research setting. Rather, their exploration is limited to determining the relation between socioeconomic status (SES) and students’ L2 achievement, motivation, learner identities, parent involvement in schooling, literacy learning, and literature interpretation and reaction. It is worth noting that SES refers to individuals’ social and economic situation and derived factors such as income, occupation, education, and financial status (Evans et al., 2022).

In this review article, an analysis of the research development on the body of literature on social class identities in S/FL educational settings is reported. Specifically, this review explores what has been researched about social class identities, as well as how and when it has been conducted. The questions guiding this exploration are: What are the predominant issues that have been approached in the examination of social class in general education and second/foreign language education? When and how have social class and class identities been addressed in the field of general education and second/foreign language education? How have social class and social class identities been conceptualized? What are the underlying theories under which social class has been addressed?

To answer these questions, a search of about 94 articles devoted to social class and social class identities was conducted, resulting in the selection of 31 research studies exploring social class (identities) in general education and second/foreign language education at both global and local levels. However, due to word limits and current-works-related policies in this journal, only 22 works will be explicitly reviewed. With the retrieval and analysis of this body of literature, this review aims to contribute to the scholarly work concerned with education and identity research, specifically on this underexamined social category, as well as provide new lenses through which it can be addressed without following canonical narratives and perspectives.

3. Methods

While database studies based on empirical and review research on SCI in teaching languages in L1 and L2 contexts were employed as an inclusion criterion, the examination of SCI outside educational contexts was selected as an exclusion criterion. The studies were grouped by theoretical perspectives of class and by context, be they L1 or L2.

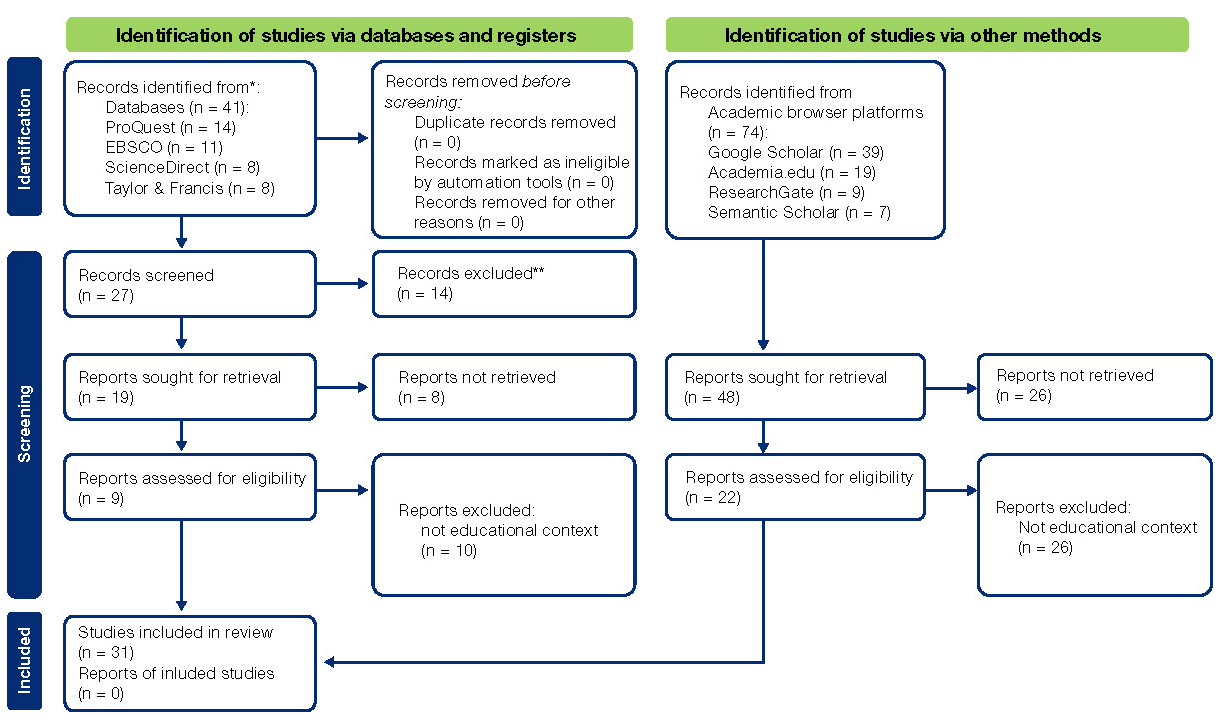

The sources used to gather studies containing these terms were the database sites ProQuest, EBSCO, ScienceDirect, and Taylor & Francis, accessed through the university. Additionally, academic social networking sites such as Academia.edu and ResearchGate, as well as the academic browsers Google Scholar and Semantic Scholar, were utilized. After excluding 21 publications due to a mismatch in titles, 94 studies were identified, and 31 research studies were selected by April 2023 (see Figure 1); however, due to word limit and current-works-related policies in this journal, only 22 works will be explicitly reviewed. The search strategies included filtering studies with the terms social class in education, social class (identities) in foreign language learning, social class identities, and identidades de clase social from 1995 to 2023. The search was limited to studies conducted before 1995.

The studies focused on how social class is shaped by power dynamics, language use, and societal expectations within educational settings. They explored how individuals negotiate and resist these influences while developing their social class identity. The search was broadened to include studies addressing social class in relation to socioeconomic status (SES) as well as in the field of sociolinguistics due to the scarcity of literature found under the initial search attempt. In obtaining data, 94 studies were first skimmed and then proofread. Subsequently, 31 resulting studies were exported to the software MAXQDA 2022, and grouped by theoretical underpinnings, with key information added as descriptions and key methodological elements as memos to facilitate filtering and summaries for presenting syntheses and displaying results of individual studies. Although no specific method was used to decide which results to collect, variables for which data were sought included (1) educational context, (2) mother tongue or second/foreign language, (3) participants’ socioeconomic status, and (4) empirical and review research.

To assess the risk of bias, the SIGN checklist for systematic reviews and meta-analyses was used for each included study. SIGN guideline development for health services collaborates with medical specialists and social care professionals to create trustworthy guidance based on evidence, aiming to create accessible recommendations to improve care in the Scottish population (SIGN, 2021). Supported by members of staff of Healthcare Improvement Scotland, the checklist is based on the AMSTAR tool, a well-known assessment tool for systematic reviews. The checklist form has 12 assessment criteria items in the internal validity section and three deliberation question items in the overall assessment of the study section, with options for high quality, acceptable, low quality and unacceptable-reject. Both sections have criteria and questions on the left and yes/no and check answer options on the right.

To answer the guiding questions of the present review article and to analyze trends among the retrieved articles, the thematic analysis process was followed. This process involves looking for patterns among the identified phrases and sentences or coded data to build more abstract categories. These categories are organized and integrated to end up with recurring broad concepts or thematic clusters (Peel, 2020).

To decide which studies were eligible, the analysis began by rereading and annotating the articles within a chart in a Word document, highlighting extracts that signaled the conceptualization of social class, the theoretical root or nature, the issues explored on it, and the followed design. Small summaries and later on phrases were generated, taking the form of trends based on the memos and syntheses carried out in the aforementioned MAXQDA software to assess the robustness of the synthesized results. Commonalities and patterns among such phrases were then identified to form more abstract categories, identifying the dominant issues researched on social class and social class identities, their conceptualizations, theoretical bases, and the methodology employed to explore them. Finally, these categories were organized and interconnected to come up with prevalent themes across the studies. These identified recurring themes included (a) social class identities formation process experienced by study-abroad and migrant subjects; (b) social class identity negotiation in classroom settings conceptualized as a sociocultural phenomenon grounded in and affecting lived experiences; (c) social class identities addressed under a decolonial critique; and (d) social class identities approached under traditional fixed categories within stratifying social structures.

Note. This diagram template was downloaded from PRISMA website and completed by the author. From The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews, by MJ Page, J.E. McKenzie, P.M. Bossuyt, I Boutron, T.C. Hoffmann, & C.D. Mulrow, 2020..

Figure 1. Flow diagram for new systematic reviews which included searches of databases, registers and other sources based on PRISMA reporting guidelines

4. Results

Before delving into the broad theme-based trends found among the retrieved studies, a brief characterization of the studies related to where, how, and when they were conducted is provided. Most of the studies (13) were conducted in the USA, followed by the UK (5) and China (3). To the best of current knowledge based on the review, only one study was conducted in each of the following countries: Australia, Canada, Brazil, Indonesia, Mexico and France. Despite a comprehensive search in Colombian academic journals in the English language education field such as PROFILE, Ikala, Colombian Applied Linguistics, How, and GIST, no studies with the related terms were found. This may imply that research production on social class identities has fallen short in South American settings.

In terms of context and population, most of the studies were qualitative case studies conducted in school settings with both primary and elementary students, as well as in university settings. A significant number of studies were also conducted on study-abroad and migrant experiences. Regarding time, it can be inferred without attempting to generalize that the exploration of social class is relatively newer in the realm of second/foreign language education than in the sociolinguistics and general education fields. Interest in social class in education seems to have started to emerge in the late 90s and has continued to grow over the past two decades, albeit at a very slow pace compared to explorations of other identity categories.

It must be noted that studies from the field of sociolinguistics will be portrayed under some of the following trends due to their significant implications for language education, as language ideologies related to language use inside educational contexts ultimately affect students’ lived experiences. In the following section, studies are reviewed to answer the research questions by providing an account of each of the particularities of the articles following the trends that emerged from the thematic analysis.

Social class identities approached under traditional fixed categories within stratifying social structures

After analyzing and reading the articles with the help of thematic analysis, three particularities were identified in these studies. First, social class is limited to socioeconomic status (SES). Second, learners' interaction and responses are analyzed based on social structure labels such as working-class or socioeconomically disadvantaged, middle-class, and upper-class or privileged. Third, social class is instrumentally addressed as a variable to determine factors such as motivation, L2 achievement, pronunciation, students' parents' investment and proficiency in L2 skills. In most of these studies, researchers start from fixed and economics-based classifications of social structures and then undertake ethnographic studies to analyze students' power relations, class-based discursive practices, language use, symbolic behavior, and aspirations.

The following ethnographic studies address linguistic variation with relatively new constructs in sociolinguistics: multimodal repertoires, stylization, and stance, with an interest in social class. It is worth noting that these studies were conducted in contexts where English is used as a mother tongue (L1).

In this tradition, Rampton (2006), drawing on relatively current thought and research, shifted from a focus exclusively on the linguistic to a focus on multimodal repertoires. He analyzed participants’ spoken English inside and outside school through recordings and contrasted the uses and features of two accents evidenced in secondary school students in London who spoke multicultural London English: Cockney English, considered a marker of working-class identity, and “posh” English, considered a middle-class identity marker by young people. He found that although both accents had different particularities that might reproduce differences among students, the students did not explicitly position themselves in terms of their working-class identities. Instead, the public constructions of their identities tended to be mediated by notions of race, ethnicity, and gender. This implies that Marx’s notion of class in itself, i.e., people’s real lived class experiences such as their work conditions, standard of living, financial situation, life chances, and everyday discourses, activities, and practices, tends to prevail over class for itself even though it is overtly evoked in everyday discourse related to social class. This study’s overall assessment of bias risk is acceptable.

Similarly, Snell (2013) sought to link working-class identities’ performance with culture and behavior by determining whether the habitual use of at least a particular aspect of interactional stance constructed a particular kind of working-class identity (e.g., characterized by humor, playfulness, the policing of social boundaries) that could be contrasted with a middle-class identity. After observing, audio recording, and analyzing the children’s interactions in their daily school activities, she claimed that non-standard local dialects of English used by working-class individuals do not have a grammar that is isolated from other varieties such as Standard English. Instead, such non-standard forms combined with a range of semiotic resources such as local vocabulary, musical influences, stock phrases, indexical meanings, and standard forms add up to working-class speakers’ linguistic repertoires. This dynamic, she argues, accounts for the creativity behind children’s linguistic choices and thus positions those working-class children as multi-skilled language users, illustrating how identities are constructed in society. This study’s overall assessment of bias risk is high quality.

Although the following studies in this same trend are not from sociolinguistics, they still consider students’ or their parents’ SES to determine the impact on second language learning motivation, achievement and proficiency in language skills.

An example is Sofyana and Pahamzah’s (2022) qualitative study. Through semi-structured interviews with six primary school English teachers, the authors sought to unveil the English teachers’ perceptions of social class influence on students’ language learning in the EFL class. Results showed that teachers believed that social class differences affected students’ language learning in the EFL class. The authors note that teachers felt that students with higher social class tended to obtain a better supportive learning environment since they have privileges at home such as technology and dictionaries with which to improve language learning and practice, which is not the case for lower class students whose parents are not sufficiently involved and do not encourage them to learn English, influencing thus language learning in the classroom. Results also revealed that teachers believed that students from different social classes differ in word use in their language communication. Students with higher-class families have better language in terms of vocabulary and pronunciation as they have access to resources such as books, movies, and people around them. Lower-class students’ lack of this access influenced their lack of words to communicate in English. The authors conclude by recommending that teachers provide intensive support and help to facilitate extra language learning for students from lower social classes. This study’s overall assessment of bias risk is acceptable.

Likewise, Liu’s (2012) large-scale quantitative survey study, for instance, examined factors that motivated middle school students from different social classes to learn English in China. Using surveys and interviews, he investigated 1,542 parents’ investment and its impact on the English learning motivation of middle school students from different social classes in China. He found that the parents’ beliefs and behaviors about investment in English education varied significantly across different social classes. The investment of upper-class parents had more positive effects on their children’s motivation in English learning than did lower-class parents’ investment; also, he found that there was more desire to study abroad and more intrinsic motivation to learn English in students from upper-class families than in those from lower-class families. This study’s overall assessment of bias risk is acceptable.

Finishing this quantitative tradition, Xu’s (2020) survey research drew on data from the Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS) in 2010 and 2013 with 10,004 participants. The author found that the objective social status of the individual, spouse, and parents all influence the subjective class identity of the individual. Therefore, Chinese class identity is family-based, not individual-based, and so the study of Chinese class identity also needs to shift from an individual perspective to a family perspective. This study’s overall assessment of bias risk is that of high quality.

Taking a different turn in terms of research tradition, Yuan (2022) interviewed two Chinese graduate students with questions related to the relationship between social class and parents’ investment, English proficiency level, and English learning motivation. The results show that the participants acknowledge that in China there exist social classes and are aware of the class they belong to. Also, they asserted parents’ knowledge, economic, and emotional investment are limited in lower-middle-class students. Lastly, they associated English learning with the possibility of entering the middle class. The author concludes by stating that class issues influence English learning experiences and the latter influences how social class identities are formed. Thus, education should take responsibility for helping students’ English learning and identity-forming, especially for the lower-middle class. This study’s overall assessment of bias risk is acceptable.

Following these qualitative interview studies, Poirier (2009) examined the intersections among social class identity development and the use and development of self-regulated learning strategies. After interviewing seven lower middle- and working-class students four times in their first year of college, they found that all the participants believed that determination would allow anyone to change his or her social class status. Such determination fueled the participants’ volition to be who they wanted to be and rise above economic circumstances and shaped the participants’ self-regulation in terms of the goals that they articulated and their self-efficacy toward achieving those goals. This study’s overall assessment of bias risk is that of high quality.

Pearce et al. (2008) is one of the few studies employing narratives to address social class identities. Drawing on Bourdieu’s notions, the authors examine social class to better understand the cultural processes of inclusion and exclusion in education with 15 working-class university students. The students’ stories showed the detrimental effects of institutional and cultural habitus on the life chances of people from working-class schools and communities. Students also entrenched stereotypes and cultural biases in education and renegotiated their own life trajectories and personal biographies. Most importantly, they also struggled back against the odds without depriving themselves of their working-class sensibilities. This study’s overall assessment of bias risk is acceptable.

The following studies share the commonality of exploring social class identity construction with privileged and global elite students. To begin with, Peck (2017) sought to explore how students’ identities related to social class are shaped and created by interviewing five upper-class students at an elite school. The author also aimed to understand how privilege is reproduced at the elite school, how students conceptualize social class and how they understand their privileged identities, as well as how lessons about global citizenship at the school unintentionally and implicitly influence students’ identity development. After criticizing that people often buy into the rhetoric of meritocracy, the author found that because of the homogeneity of the community consisting of students’ socioeconomic similarities, they are unable to question the status quo and engage critically about their privilege. Also, students are aware of the bubble they live in and the culture and image that less privileged people have about them while also claiming that the school expects everyone to look similar and adopt the ideologies of administrators and teachers. Further, students expressed their school does not uphold the tolerance, fair play, and honesty pillars it claims to represent. This study’s overall assessment of bias risk is acceptable.

Vandrick (2011) also explored social class identity with global elite students at a private university. She outlined two main themes that emerged from their interviews and conversations with the four privileged students: (1) their strong sense of responsibility with their families and regarding their privilege, in which they felt self-assured and comfortable with their role in the world, and (2) their sense of where they belonged in the world, which entails almost all of them want to come back to their home countries and work in their parents’ business. The author concludes by suggesting educators educate them to be analytical, critical, and aware, and to help them understand their privileged positions and the related implications and consequent responsibilities. Such education may help them use their privileged positions for good and prepare for their future as these students will likely have strong power and influence in the world and may represent a future kind of globalization. This study’s overall assessment of bias risk is acceptable.

Social class identity negotiation in classroom settings is conceptualized as a sociocultural phenomenon grounded in and affecting lived experiences

Unlike the studies comprising the previous trend, these studies deem class identity as beyond notions of economic capital or SES, beyond fixed stratifying categories, and beyond deterministic approaches. In other words, these studies are more aligned with my perspectives and conceptualization of social class identity as performed and enacted, as well as grounded in students’ histories and lived experiences related to social class. Most of these studies analyze the discursive practices, ideologies, and classroom experiences related to social class positionings and enacted practices mediated by power relations that emerge in interactions, language tasks, literacy practices, and project work.

A starting example is Astarita’s (2015) mixed-methods study employing an online survey, semi-structured interview, and document analysis of Avanti! with an initial 101 and later 16 college students. The study sought to understand whether and how a perceived middle-class worldview in the foreign language curriculum, coupled with approaches to language teaching that emphasize speaking about oneself (i.e., CLT), impacted learners from different social class backgrounds. Results showed that socioeconomic differences are highlighted by activities that elicit personal information. Also, self-identified lower- and upper-class participants reported divergent classroom experiences in terms of how comfortable, valued, part of the group, adequate, and heard they felt. Finally, some participants indicated their beginning Italian textbook represented the diverse socioeconomic statuses of native speakers differed by first-generation status. This study’s overall assessment of bias risk is acceptable.

Similar to the previous study in terms of design, Thomas and Azmitia’s (2014) mixed-methods study, drawing on the social identity theory (which posits that social categories are more salient to low-status individuals) and the concept of centrality, examined the social class experiences, the interpretations of those experiences, and the possible importance of social class identity over gender and ethnicity of 160 ethnically and socioeconomically diverse men and women through interviews and surveys. Results show that regardless of socioeconomic status, participants rated social class as affecting their everyday experiences more than gender or ethnicity. However, the narratives of upper-class and working-class students differed in the emotions that were expressed concerning their social class circumstances. While the former expressed emotions of guilt, luck, blessed, and feeling fortunate, the latter used emotional terms such as anger and pride. The authors criticized that class is a taboo topic in the US and that it is important to understand how social class identity becomes salient, the meanings people assign to it, and its centrality relative to other social identities. This study’s overall assessment of bias risk is acceptable.

Similarly, Gao’s (2010) ethnographic case study with six affluent Chinese participants in three language schools in the UK gives an account of not only how social-class status influenced the learning of English but also how learning English affected social-class status. Once the learners realized the sociocultural and language opportunities of the middle and upper class in Britain and were influenced by language teachers, peers, the media, and the social environment, they decided to enact and reinforce their privileged class identities. He then concludes that learners’ opportunities for practicing English and friendship networking were affected by their self-identified social class positions. This study’s overall assessment of bias risk is acceptable.

Payne-Bourcy and Chandler-Olcott’s (2003) longitudinal case study reported how Crystal, a working-class rural adolescent student, perceived and experienced the relationships between social class and her language and literacy practices as she moved from high school in her isolated rural community where she grew up to college in an urban environment. Although Crystal was a successful learner by most conventional standards, she struggled to stay in school and to adopt the dominant discourses of postsecondary education. As a rural high school student, she used a variety of language and literacy practices to “pose” as middle class. When she crossed to college, some of these practices served her better than others. Ultimately, she became alienated by college courses that did not acknowledge language competencies related to her status as a working-class person and that did not allow links between her interests in popular culture and her formal assignments. This study’s overall assessment of bias risk is acceptable.

In the same fashion, Thein et al. (2012) studied for six weeks the participation of four white socioeconomically diverse students participating and interpreting in a literature circle about a text dealing with social class. The authors emphasize considering social class thoroughly in English language education, especially as it affects literary interpretation. Findings revealed that participants’ social class identity performance was nuanced. Although easily categorized as working class or middle class at first glance, the four students performed four distinct class identities based on their diverse sets of experiences in their community, showing thus the complexity of social class among the students. In the literature circle discussions, the students positioned themselves and each other in ways that were consistent with and reflective of their class identity performances in their larger school community and family worlds. However, their responses reflected specific social class identity performances grounded in the history of each student’s local lived experiences in a socioeconomically divided community. The authors conclude that social class is a complex phenomenon grounded in local experiences in families and communities and reflected at school, and thus exhort teachers to include social class discussions to help learners critically examine race, gender, and class and how their structures impact their identities. This study’s overall assessment of bias risk is acceptable.

In a similar case but with a larger population, Preece (2018) conducted a longitudinal ethnography with 93 first-year working-class undergraduate students of an academic writing program in an EAP context. The author took an intersectional approach to study how the participants performed gender and class interactions and discussions in academic writing tasks. Results show that academic writing shapes gender and class identities in tutoring sessions, dialogue with the self about the imagined audience, and in the ongoing proceedings of the academic writing classroom. This study’s overall assessment of bias risk is acceptable.

Following a Bourdieusian notion of class, Palmer (2018) compared the identities, beliefs, and factors of social class of 12 students of English as an additional language divided into two groups in two contexts: immigrant students to the United States and Brazilian students, both groups in their first year at a public high school from low socioeconomic neighborhoods. Results have suggested English is expressed as a form of capital and a cyclical relationship between beliefs, identities, and social class. Access to English capital seems to affect both personal and societal beliefs about English learning, which in turn affects the efforts to access the English-speaking world in different manners and degrees. While the immigrant students to the United States make efforts to enter the inner circle of English speakers in their community, the Brazilian students either adhere to the beliefs within their social class that English is inaccessible to them or they try to break out of the cycle by investing in the imagined community of English speakers. This study’s overall assessment of bias risk is acceptable.

To finish describing the studies in this trend/theme, Hunt and Seiver (2017) explored how social class discourses are reproduced, resisted, and appropriated in the past two decades within the setting of K-12 in the US. The authors claim that social class matters when it comes to inequalities in terms of school performance and access to educational resources between middle-class and poor students, as well as to teachers, families, and students’ understanding of the world, self, and others. The analysis of the reviewed studies showed that deficit discourses about poorly resourced students and families related to laziness, impulsiveness, cognitive deficiency, and not valuing education are based on the American doctrine of individualism and meritocracy, which are accepted by educators. In turn, class-based assumptions held by teachers are influenced by stereotypes and classism, which influenced how they interpreted instructional practices, interactions, and students’ abilities, successes, and failures, as well as the usage of data from assessments to make instructional decisions, which end up marginalizing poor students. The authors also found that the curriculum for poorly resourced students is limited compared to middle- and upper-class students whose lived experiences and ways of understanding are more favored. Despite such inequalities and reproduction of dominant discourses, some studies showed poor students’ agency and negotiation when interacting with such discourses as they performed hybrid class identities, resisted deficit discourses, and explored class status and relations. This study’s overall assessment of bias risk is acceptable.

Social class identity construction process experienced by study-abroad and migrant subjects

To begin with, Darvin and Norton (2014) carried out a case study with two very different adolescent Filipino migrants in Canada. Drawing on Bourdieusian views of social class, they compared the language and literacy practices of both boys with different socioeconomic backgrounds. Although both came from the same country and both had to negotiate a transnational habitus, the social and learning experiences and opportunities of the privileged student were more successful due to his class positioning. Similarly, Block (2012) conducted an ethnographic case study. Drawing on participant-generated data collection with three Spanish-speaking migrant Latinos in the UK for 12 months focusing on the story of Carlos, a forty-two-year-old Colombian upper-middle-class migrant in London since 2001. After analyzing Carlos’s conversations at work and home and for interviews with the researcher, the author notes that the participant underwent “declassing” as he went from being a PhD lecturer to a porter at a building due to his poor English language skills. He struggled to identify and invest too much in conversations to practice his English with his co-workers who had a working-class habitus. However, in terms of consumption patterns and symbolic behavior, Carlos’s lifestyle away from work is still associated with the middle class. The author concludes by interlinking Carlos’s class identities with other categories such as ethnicity and gender. This study’s overall assessment of bias risk is that of high quality.

Relevant to this theme and conceptualizing social class under a Bourdieusian notion of capitals combined with the concept of imagined communities, Bruce (2014) examines ten ethnographic studies that either overtly or covertly highlight social class as a support or a barrier to acquiring an L2. Such studies comprised the two categories of study abroad L2 learners and immigrant learners looking both at highly privileged and underprivileged learners. The author concludes that social class privilege – or the lack of it – impacts the learning practices of students, impairs, or enhances affective factors such as confidence, and informs how much – or little – parents are involved in their child’s education and the results of this involvement, and impacts whether one can afford L2 classes and/or the transportation and childcare costs that incur while attending an L2 class. The author also remarks that linguistic features such as accent and code-switching mark our social class and contribute to the suppression of moving out of that marked social class. The author finally calls for educators to consider class in language learning practices to understand the dynamics played out among L2 learners in the classroom to cultivate an awareness of their own social class positioning and how their roles in this world impact others. This study’s overall assessment of bias risk is acceptable.

Social class identity addressed under a decolonial critique

This trend was intentionally left last given its nature compared to the studies presented above. As could be seen, most studies followed tenets of power relations denouncing and claiming for social justice and equality of critical theory. However, López-Gopar and Sughrua (2014) problematized identity construction processes related to social class with a decolonial critique regarding it as a colonial difference element. They provided a historical overview of this social category concerning coloniality. Also, they discuss how social class has impacted English language education access, Mexican teachers of English, and curricula. They note that these teachers have been affected in many ways, such as the intrusion of the English language and its connection with globalization and neoliberalism, exploitation in private English institutions, and coloniality reflected in values and life experiences of the middle- and upper-class in English textbooks. Thus, teachers have the responsibility to avoid the perpetuation of the gap between social classes. Finally, they call for critical engagement in and problematization of social class issues in English language education using research, contesting and participating in language policies, engaging in educational initiatives, and curriculum development. This study’s overall assessment of bias risk is acceptable.

5. Discussion

The results of this review carried out above show that the scholarly interest in social class as an identity inscription in educational contexts may have begun by the late 90s and has continued to grow slowly up to the present day. Also, although scholarly work on social class has evidently been conducted in L2 contexts, it has mainly been geo- and body-politically located in English-speaking Western and European countries; thus, more examination of class identities in FL contexts should be carried out, especially in the Global South. Moreover, predominant issues that scholarly work has addressed in the examination of social class within educational contexts deal with power relations, negotiation of self-identified and assigned class positionings, class-based discursive practices and ideologies mediated in literacy practices and language tasks, as well as the performance of class identities through enacted practices in and out of the school and college. Likewise, scholarship has explored the experiences of students in study-abroad and migrant settings, as well as the overt college students’ critical insights and perspectives of the effects of the socioeconomic status and stratum of people. In terms of social class conceptualization, the findings showed that while some scholarship deems social class merely as SES, a fixed category of social structure, and an instrument to determine factors such as language proficiency, motivation, L2 achievement, and parental involvement (Rampton, 2006; Snell, 2013; Liu, 2012; Xu, 2020), some other portions of scholarship regard it as a socio-cultural phenomenon that is performed through enacted practices that can be observed through social networking, power discourse, ideologies, and symbolic behavior and consumption patterns (Astarita, 2015; Gao, 2010; Palmer, 2018; Thein et al., 2012; Thomas & Azmitia, 2014), all of which are grounded in agents’ history and lived experiences.

Results showed that social class identity development has been mainly addressed under a critical theory framework. This fact is a key factor in the identification of the research void as a product of this profiling work since it is timely to establish that more work on social class exploration under decolonial lenses should be done. This can shed light not only on the similar and already-found unequal dynamics of power relations among agents but also go beyond by unveiling the effects and injuries that global practices and discourses such as neoliberalism and global capitalism have caused. In other words, addressing social class identities from a decolonial gaze hidden wounds that the colonial legacy has caused can be made observable, allowing us all to (a) see the ways we as individuals from the peripheries have been subjugated, (b) agentically enable our global south subjectivities to start taking political action that leads us to subvert both larger societal inequalities and colonial wounds related to Euro-USA-centered views on social class.

This review has limitations in terms of the number of studies, methods, and statistical analysis. Although social class (identity) is greatly examined in different fields such as sociolinguistics and anthropology, there is a scarcity of research in the education field resulting in a somewhat reduced number of scholarly works on this phenomenon, especially in the Latin American and Caribbean contexts. Likewise, although this study is rooted in the qualitative tradition of research with a transition towards decolonial stances, more methods and statistical analyses could have been employed to realize data validity and reliability in the included studies. Further research is exhorted to review more than 30 studies in a greater repertoire of not only databases but other sources as well as include rigorous methods and numerical examination of the reviewed studies.

References

Ardoin, S. (2021). The nuances of first-generation college students’ social class identity. In R. Longwell-Grice & H. Longwell-Grice (Eds.), At the intersection: Understanding and supporting first-generation students (pp. 89-99). Routledge. https://r.issu.edu.do/YR

Astarita, A. (2015). Social class and foreign language learning experiences [Unpublished doctoral thesis]. The University of Wisconsin-Madison. https://r.issu.edu.do/j3

Block, D. (2012). Class and SLA: Making Connections. Language Teaching Research, 16, 188–205. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168811428418

Block, D. (2020). The political economy of language education research (or the lack thereof): Nancy Fraser and the case of translanguaging. In Nancy Fraser, Social Justice and Education (pp. 119-139). Routledge. https://r.issu.edu.do/87

Bonilla-Medina, S., Varela, K., & García, K. (2021). Configuration of racial identities of learners of English. Profile: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 23(2), 137–150. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v23n2.90374

Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In J. G. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education (pp. 241–258). Greenwood. https://r.issu.edu.do/4p

Bruce, S. (2014). Why Class Matters: Identity Construction and Privilege in Second Language Acquisition. [Unpublished manuscript]. https://r.issu.edu.do/NE

Butler, J. (2021). Bodies that still matter. In A. Halsema, K. Kwastek, & R. van den Oever (Eds.), Bodies That Still Matter. Resonances of the Work of Judith Butler (pp. 177-93). Amsterdam University Press. https://r.issu.edu.do/Mr

Castañeda-Peña, H. (2021). Local identity studies of gender diversity and sexual orientation in ELT. HOW, 28(3), 154-172. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.28.3.683

Darvin, R. & Norton, B. (2014). Social Class, Identity, and Migrant Students. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 13(2), 111-117. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2014.901823

De Costa, P., & Green-Eneix, C. (2021). Identity in SLA and second language teacher education. Research questions in language education and applied linguistics: A reference guide, 537-541. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-79143-8_94

Evans, O., McGuffog, R., Gendi, M., & Rubin, M. (2022). A first-class measure: Evidence for a Comprehensive Social Class Scale in higher education populations. Research in Higher Education, 63(8), 1427-1452. https://r.issu.edu.do/7m

Fraser, N. (2020). From redistribution to recognition?: Dilemmas of justice in a ‘postsocialist’ age. In The new social theory reader (pp. 188-196). Routledge. https://r.issu.edu.do/rv

Gao, F. (2010). Negotiation of Chinese learners’ social class identities in their English language learning journeys in Britain. Journal of Cambridge Studies, 5(2-3), 64–77. https://doi.org/10.17863/CAM.1357

Gilleard, C. (2020). Bourdieu’s forms of capital and the stratification of later life. Journal of Aging Studies, 53, 100851. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2020.100851

Guevara, J. (2018). Construcción de identidades de clase social a través de las prácticas de estudiantes de pregrado de la Facultad de Ciencias Sociales de la Universidad de los Andes [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Universidad de los Andes, Bogotá, Colombia. https://r.issu.edu.do/b7s

Hunt, C., & Seiver, M. (2017). Social class matters: class identities and discourses in educational contexts. Educational Review, 70(3), 342-357. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2017.1316240

Jiang, L., Yang, M., & Yu, S. (2020). Chinese ethnic minority students’ investment in English learning empowered by digital multimodal composing. TESOL Quarterly, 54(4), 954-979. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.566

Jones, L. (2019). The ‘C-Word’: novice teachers, class identities and class strategising. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 27(4), 595-611. https://r.issu.edu.do/KI

Knisely, K. A., & Paiz, J. M. (2021). Bringing trans, non-binary, and queer understandings to bear in language education. Critical Multilingualism Studies, 9(1), 23-45. https://r.issu.edu.do/52

Kramsch, C. (2019). Between globalization and decolonization: Foreign languages in the cross-fire. In Decolonizing foreign language education (pp. 50-72). Routledge. https://r.issu.edu.do/Yh

Lansley, S. (2019). The ‘distribution question’: measuring and evaluating trends in inequality. In Data in Society (pp. 187-198). Policy Press. https://doi.org/10.1332/policypress/9781447348214.003.0015

Lawrence, L., & Nagashima, Y. (2020). The intersectionality of gender, sexuality, race, and native-speakerness: Investigating ELT teacher identity through duoethnography. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 19(1), 42-55. https://r.issu.edu.do/TR

Liu, G., & Darvin, R. (2024). From rural China to the digital wilds: Negotiating digital repertoires to claim the right to speak. TESOL quarterly, 58(1), 334-362. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.3233

Liu, H. G. (2012). Parental investment and junior high school students’ English learning motivation: A social class perspective [Unpublished doctoral Thesis]. Peking University, Beijing, China. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2014.901820

López Gopar, M., & Sughrua, W. (2014). Social Class in English Language Education in Oaxaca, Mexico. Journal of Language, Identity, and Education, 13(2), 104-110. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2014.901822

Marx, K. (2020). The XVIII Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. e-artnow. https://r.issu.edu.do/Ws

Norton, B. (2019). Identity and language learning: A 2019 retrospective account. Canadian Modern Language Review, 75(4), 299-307. https://doi.org/10.3138/cmlr.2019-0287

Page, M., McKenzie, J., Bossuyt, P., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T., & Mulrow, C. (2020). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Palmer, M. (2018). Beliefs, identities and social class of English language learners: a comparative study between the United States and Brasil [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Universidade Federal de Viçosa, Minas Gerais, Brazil. https://dx.doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.30728.52487

Payne-Bourcy, L., & Chandler-Olcott, K. (2003). Spotlighting Social Class: An Exploration of One Adolescent’s Language and Literacy Practices. Journal of Literacy Research, 35(1), 551-590. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15548430jlr3501_2

Pearce, J., Down, B., & Moore, E. (2008). Social Class, Identity and the “Good” Student: Negotiating University Culture. Australian Journal of Education, 52(3), 257-271. https://doi.org/10.1177/000494410805200304

Peck, S. (2017). Social Class Identity Development and Elite Schools. Honors Theses. Paper 842. https://r.issu.edu.do/gI

Peel, K. (2020). A beginner’s guide to applied educational research using thematic analysis. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 25(1), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.7275/ryr5-k983

Pérez Ahumada, P., & Andrade, V. (2021). Class identity in times of social mobilization and labor union revitalization: Evidence from the case of Chile (2009–2019). Current Sociology, 71(6), 1040-1062. https://doi.org/10.1177/00113921211056052

Poirier, R. (2009). Exploring the intersections of social class, identity, and self-regulation during the transition from high school to college dissertation [Unpublished doctoral thesis]. The Ohio State University, Ohio, USA. https://r.issu.edu.do/oh

Preece, S. (2018). Identity work in the academic writing classroom: Where gender meets social class. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 32, 9-20 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2018.03.004

Rampton, B. (2006). Language in late modernity: Interaction in an urban school. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13670050802149416

SIGN (2021). SIGN makes sense of evidence. https://www.sign.ac.uk

Snell, J. (2013). Dialect, interaction and class positioning at school: From deficit to difference to repertoire. Language and Education, 27, 110-128. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2012.760584

Sofyana and Pahamzah (2022). Social Class and EFL Learning in Indonesia: Listening to Teachers’ Perception. JELTS, 5(1), 91-101. https://dx.doi.org/10.48181/jelts.v5i1.16182

Stubager, R., & Harrits, G. S. (2022). Dimensions of class identification? On the roots and effects of class identity. The British Journal of Sociology, 73(5), 942-958. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12977

Thein, A., Guise, M., & Sloan, D. (2012). Exploring the Significance of Social Class Identity Performance in the English Classroom: A Case Study Analysis of a Literature Circle Discussion. English Education, 44(3), 215–253. https://r.issu.edu.do/c1

Thomas, V., & Azmitia, M. (2014). Does Class Matter? The Centrality and Meaning of Social Class Identity in Emerging Adulthood. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research, 14(3), 195-213. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15283488.2014.921171

Vandrick, S. (2011). Students of the new global elite. TESOL Quarterly 45(1), 160-169. https://r.issu.edu.do/In

Vanke, A. (2023). Researching Lay Perceptions of Inequality through Images of Society: Compliance, Inversion and Subversion of Power Hierarchies. Sociology. https://doi.org/10.1177/00380385231194867

Von Esch, K. S., Motha, S., & Kubota, R. (2020). Race and language teaching. Language Teaching, 53(4), 391-421. https://r.issu.edu.do/kR

Weber, M. (2019). Economy and society: A new translation. Harvard University Press. https://r.issu.edu.do/nK

Xu, Q. (2020). “Mixed” subjective class identity: a new interpretation of Chinese class identity. The journal of Chinese sociology, 7(9), 1-24.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s40711-020-00122-x

Yuan, J. (2022). Social-Class Identity and English Learning: Importance of Education. United International Research for Research & Technology, 3(6), 65-68. https://r.issu.edu.do/dL

Other Information

This review is part of the dissertation I undertake as a doctoral student at the Doctorado Interinstitucional en Educación program from Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas in Bogotá, Colombia. I hereby note that this review is not registered. Also, a protocol was not prepared. As for support, it must be stated that this review was not supported either by financial or non-financial funders or sponsors. Likewise, I, the only reviewer, do not have any competing interests in this manuscript. Finally, template data collection forms, data extracted from included studies, data used for all analyses, analytic code, or any other materials used in the review are not publicly available.

Author contributions

Conceptualization; methodology; software; validation; formal analysis; research; resources; data curation; writing (original draft); writing (proofreading and editing); visualization; supervision; project administration: L.K.